From Dayton, Ohio to Donald Trump

Why our obsession with efficiency is incompatible with democracy

I grew up in Kettering, Ohio, a middle-class suburb of Dayton, a typical rust belt city in that part of the country. My memories of the town were formed and deepened for the most part over a 10-15 year period that spanned the mid-to-late ‘80’s and up through the end of the century--a timespan in which I went from being a child to a high school graduate and then college student at the nearby “cow college” of Miami University (of Ohio).

I look back on this span now as a time when the world made sense to me. Which is only to say I was young and had formed a feeling about the world that seemed permanent.

A 15-minute drive from my childhood home stood a sprawling GM plant, which was active then and which I can vaguely remember visiting on a school field trip. The plant would be closed, and its small army of employees out of work, by the end of the ’90s. It would sit empty for another decade after that, with a small part of it being eventually bought up by a Chinese-run glass manufacturer.

There were other industrial businesses there as well, such as National Cash Register, which was at one time a major industrial engine in Dayton. It, too, would close down and move elsewhere, as it seemed anything productive and useful would end up doing before long. Eventually, it would begin to feel to me like the entire area was simply an air force base (Wright-Patterson) connected to shopping malls.

In our suburb of Kettering, the only independent businesses I can remember visiting were a couple of run-down barber shops, a taekwondo studio, a pizza place, and a few Chinese restaurants. There was a mid-size, independent, upscale grocery store in the suburb just south of ours, though our house was right by the Kroger’s we would usually go to. If we needed a lot of groceries, or the money was tight, we would drive about 25 minutes to Cub Foods, a sprawling warehouse-style Costco-esque store that was short on amenities, long on bargains.

The food I remember eating the most was simply what was most readily available and cheapest: Wendy’s, Burger King, Taco Bell, McDonald’s. If we wanted a fancy meal we might go to Applebee’s or Outback Steakhouse or the Olive Garden. Typically this would only happen for lunch, because lunch is cheaper than dinner.

In the years after I moved away and returned to visit, I’d drive around town and mark the changing development in terms of chains swapping out for other chains. Oh, that Taco Bell is now a Starbucks? Wow, that Arby’s is now a Wendy’s?

I can still remember when the first “super store” went in. A Meijer. Its sprawling interior was essentially a town unto itself. You could buy groceries, shop for clothes, pick up pet supplies, find insect repellant, grab a couple magazines, and get a bite to eat at the food court without ever leaving the grounds. This type of store is now so commonplace it’s hard to fathom it being newsworthy, but at the time our town hadn’t seen anything like it. The grand opening was reported on by all the local stations, and the company set up searchlights in the parking lot. The zig zagging columns of light could be seen for miles.

It was hard to imagine at the time that this was anything but an excellent new addition to our hometown. I can remember wandering around its vast interior with my mom and brothers, and then driving across the expansive parking lot afterwards to grab some food at McDonald’s.

The store seemed to represent progress itself. Convenience--and low, low prices--or so we were told, was our birthright. But even beyond that, it was said to represent an unstoppable and seemingly organic, even biological, evolution. Thanks to sweeping deregulation, markets were now free, free at last, and life itself would get easier, more convenient, and cheap.

One key underpinning of this evolutionary process was a belief that efficiency, in the end, was really what mattered. It was efficiency that would bring costs down. Efficiency that would allow us to live more comfortably, surrounded by an ever-growing pile of more--more of everything we desired, be it jackets, T-shirts, burritos, hand tools, mobile phones, computers, backpacks, or shoes. The American people would now be empowered to glide freely across this efficient, low-cost highway toward a bright, exquisitely comfortable low-cost future.

Of course, efficiency would require the formation and merging of massive corporations, requiring the use of massive tracts of land, and the creation of massive global supply chains requiring the burning of massive amounts of energy. And a hefty dose of outsourcing. There were a few objections, though seemingly none that mattered, and they were quickly explained away with hand-wavey arguments.

The arguments in favor typically centered on the supposed benefit to “consumer welfare” in terms of low costs, or took a cynical “realist” approach that this shift was simply the inevitable result of “the market” at work. But ultimately, the trump card would be the fact that these large corporations were just so damn efficient. Sure, it might cost us a handful of jobs here and there, but only by leveraging such massive scale will these corporations truly be able to shave a penny here and a penny there off the piles of stuff we consumers were all so desperate to accumulate.

Though I was a young kid at the time, I can clearly remember a sense of uneasiness as this shift took place. Through the window of whatever beat-up minivan my parents drove at that time, I watched with puzzled despair as huge tracts of land off the highway were converted from farms or woods or rolling fields into unnervingly identical houses packed into tight lots.

It was the sameness that got to me. The lack not just of character, but of care and imagination. The complete erasure of the subtle and indefinable human touch. To me, they represented an insistence, even a triumph, of efficiency over all else.

The rationale, or so I imagined, was that while it might be possible to build more interesting and unique houses, or houses that were built with better materials and would therefore last longer, doing so would cost both time and money. And both money and time are, in the end, money. And the whole point of efficiency was, most critically, to save money.

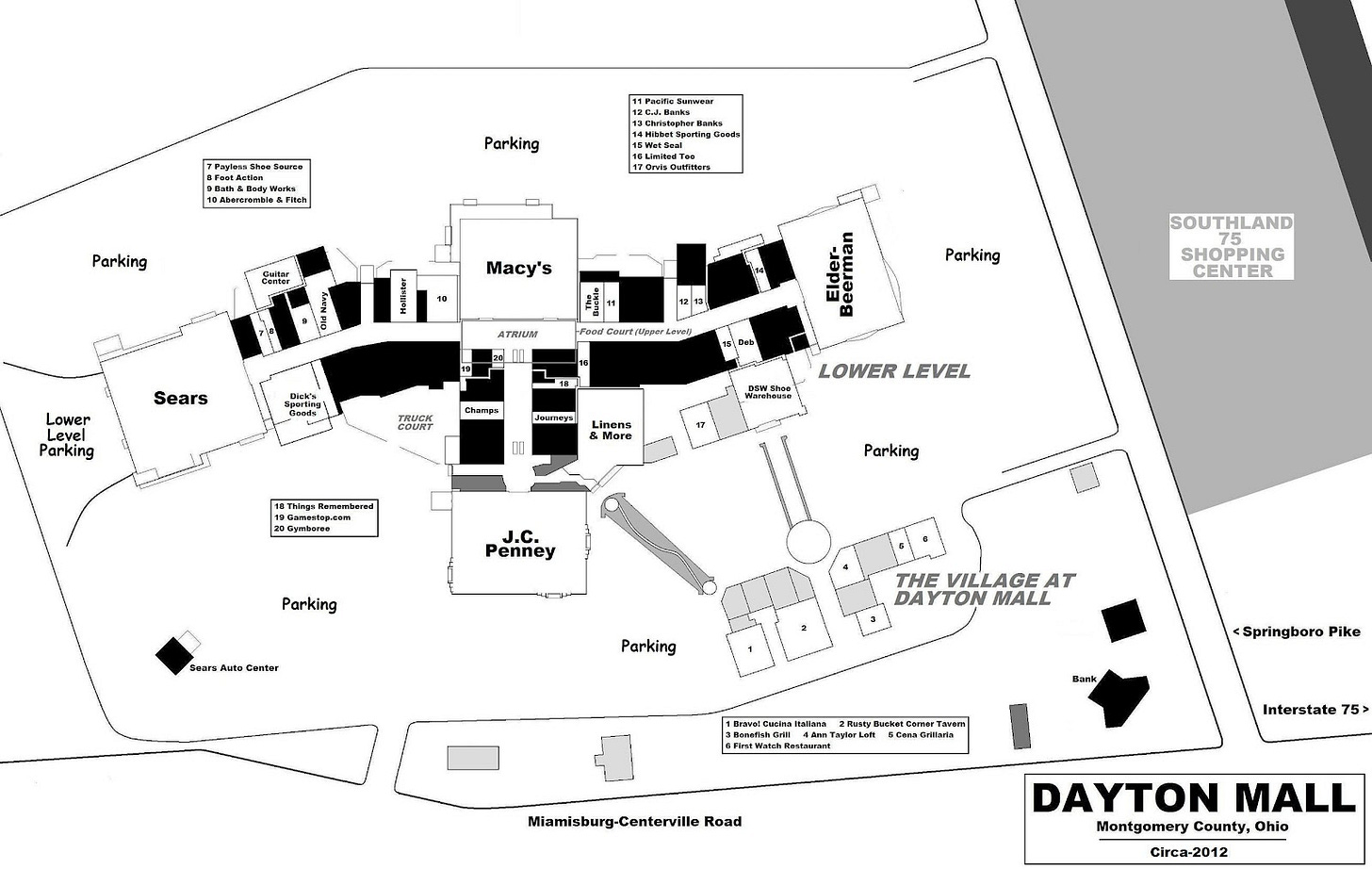

I can remember family trips to the Dayton Mall, a sprawling retail compound that from overhead could easily be mistaken for a military complex. The mall itself was encircled by vast parking lots, which themselves were encircled by waves of strip malls, all efficiently planned and constructed--meaning, of course, that every building resembled a giant, hollowed-out cinder block, without adornment of any kind save for the shop’s name in bold letters across the building’s facade. Kmart, Marshall’s, TJ Max, PetSmart, Best Buy.

As this type of construction charged forward seemingly unimpeded, I began to form a vague notion. The gray, prefabricated buildings called to my mind what I had seen in newspapers and books about “Soviet-style” architecture. “Functional,” one might generously say, built as rapidly and cheaply as possible, with the end goal of doing whatever it was intended to do in the most efficient manner possible. Whether it was storing bread or storing people, the idea seemed to be that it needed to be done as cheaply and as quickly as technology would allow. Taking the time and added expense to create a building one might actually desire to look at and live in was, I’m sure, dismissed in the Soviet Union as a bourgeois luxury and actual impediment to the economic growth of a superpower.

Fellow travelers, I’d say, in the cult of efficiency.

And I don’t say that lightly or mean to imply we’ve merely adopted a shared aesthetic as an unhappy accident. In fact, since the anti-antitrust Reagan revolution of the ’80s and the deregulation bonanza of the Clinton years and leading right up to the present moment, our economic engine has increasingly begun to resemble a “Soviet-style” economy.

Following forty years of unchecked mergers, acquisitions, predatory pricing practices, relentless offshoring, union busting, and leveraged buyouts, our economy has become the type of centralized, command-and-control operation that free market fundamentalism was intended to abolish, or so we were told.

Our economy, of course, is not run by government officials in the Politburo. Rather, it’s run by a coalition of unelected, private governments. Towering, bureaucratic corporations with brilliant (and expensive) branding and PR that’s intentionally and strategically deployed to hide their harsh, brutally efficient trade practices.

We have the Department of Online Retail and Shipping (Amazon), the Department of In-person Retail (Walmart and Target and Costco), the Department of Information (Google, which also means YouTube, and Facebook, which also means Instagram and WhatsApp, plus Murdoch et al), the Department of Finance (Chase, Wells Fargo, BoA), the Department of Foodstuffs (Cargill, Monsanto, Coke, Pepsi), and so on.

While none of these giant corporations have captured 100% of the market share (yet), they each function—singularly, and together as a group—in such a way as to create what amounts to a shared corporate bureaucracy that, by any measure, dominates, controls, and engineers the supposedly free markets they operate within. This bureaucratic monopolization spans the entire supply chain, from production, to transportation and distribution, to the stores where “stuff” is sold, and ultimately, to us.

What little choice we have left as consumers is often quite simply an illusion. Choosing to shop at Banana Republic, for example, over Old Navy or GAP, all of which are owned by the same multinational corporation—GAP, Inc, which also owns Athleta, Piperlime, and five other retail chains. Or choosing to get your groceries at Albertsons over Safeway or Von’s. Again, same company. Albertsons actually owns 20 different grocery chains.

In effect, I can walk into any grocery chain nationwide, owned by whichever giant corporation, and find the same dizzying array of breakfast cereals—all the same (often GMO) wheat- and corn-based crunch balls with wildly different branding and “flavors” that mask their fundamental sameness—nearly all of which are made by one of three companies, as well as the same brands of toilet paper, and cheese, and meat, making any difference between the chains nominal at best.

This is efficient in a linear sense. Once you’ve established what amounts to a world-spanning factory line from producer to consumer, it moves quite efficiently. That is, until the real-world variables and assumptions it was created within change overnight, as in the case of a global pandemic or other crisis. When flexibility and variability are suddenly needed, as it will inevitably be, the factory seizes up. Failures at any point within the factory line create cascading failures across the factory line. And because so many of these bureaucratic corporate governments share both production and distribution resources, these cascading failures can quickly collapse the system as a whole.

On the nominal end, it could mean that Banana Republic, GAP, and Old Navy (and any other large retail chains that share their production and distribution lines) don’t receive the jackets, T-shirts, and hoodies they were expecting on time. On the more severe end, it means food production systems, engineered for linear mass production, are “forced” (through bottom-line bureaucratic priorities) to liquidize and destroy actual food and/or animals, on account of bottlenecks in distribution.

For example, at the start of the pandemic, as distribution chains began seizing up and restaurants were forced to shut, dairy plants were “forced” to pour thousands of gallons of milk down drains. A perhaps more vivid and chilling demonstration, and this is just one small example, Cargill was “forced” to close an egg liquidizing plant in Minnesota, resulting in the euthanization of the 61,000 hens that supplied eggs to that plant, against the farmer’s wishes, on just one contracted “farm.”

At the same time as food producers were forced to destroy the food they were producing, grocery shelves across the country were picked clean, creating mass fear and anxiety in a population already reeling from spiraling infection rates and closing businesses. Individuals were accused of creating a “false” food crisis on account of “panic buying” and “hoarding,” but the reality was an actual food shortage, brought on by an “efficient” food factory built without redundancy and resiliency.

What was dismissed as selfish “hoarding” was not only a natural and proper reaction to having to wait 30-60 minutes to get into a grocery store, only to find empty shelves once you got in; it was also official government advice, as we were explicitly instructed overnight to keep 2-3 weeks of food on hand. There wasn’t enough food, because the corporate food system couldn’t keep up. The reason it couldn’t keep up is simply because it was designed to be “lean,” “efficient”, and deliver “just-in-time” shipments. Which is just to say it demands an unbroken, continuously functioning world whose variables don’t change much from day to day. This being, as is quite undeniable now, a fantasy.

By contrast, many independently run farms, on account of being decentralized, multi-crop, and local, were able to quickly adjust and sell directly to consumers through farm boxes, CSAs, and farmers markets. It’s not much of an imaginative leap to say that if these independent farms made up a much larger, if not exclusive, share of farms across the country, it would be possible to eliminate, or at the very least severely mitigate, the impact of future crises or disruptions to corporate supply chains that will inevitably arise down the road.

As an aside, the argument that independently-run, small farms are not “scalable” seems to me shortsighted, for a couple of reasons. For starters, the current food system, which includes the quantity of food produced along with land use volume and employment numbers, should not be the measure we use to decide on the amount of food we need—as it currently “efficiently” generates an excessive amount of cheap, calorically-dense items that have spawned their own pandemic, in the form of obesity and its coinciding chronic conditions like heart disease and diabetes. Fighting against this pandemic has been expensive, wasteful, deadly, inefficient, and tragic—both physically and mentally.

Second, while industrial farming might “efficiently” increase yields per square yard in the short term, it does so at the expense of preserving the topsoil and water table over the long term. What good could possibly come of creating more food now if the trade off is no food later?

Third, looking at land use and employment numbers based on the current system will present incompatible comparisons. With agriculture leadership at a government level that actually encouraged and supported small-scale farmers at a policy level, while eliminating or reducing the monopolization of viable farmland by large corporations—including land currently used for things like massive Amazon warehouses—it’s possible to create a vibrant ecosystem of small-scale, owner-run farms. Thus creating sustainably grown, local food, along with new opportunities for meaningful work through self-employment.

--

If efficiency is the only economic measure we choose to care about, the end result of such a decision extends far beyond mere aesthetics. Rather, it creates a type of economic engine that demands a brutal aesthetic as a necessary function or byproduct of its actual operation. Efficient buildings, efficient housing, efficient farming, efficient transportation. And let us not forget, efficient employees—and yes, efficient consumers.

Efficient here meaning, of course, uniform, predictable, replaceable, cheap.

What had once been an intentionally decentralized economic engine—a New Deal-era prime directive undertaken and largely achieved with great difficulty—is now rapidly approaching a centralized one. Where we once had scores of small businesses, often run by sole proprietors, their share of the market has been increasingly and intentionally swallowed up by corporations whose end game, by virtue of our unstructured and unregulated markets, requires them to dominate, lest they themselves be dominated by even larger companies.

What this ultimately translates to is a closing off of “the commons” to regular Americans and would-be entrepreneurs (who aren’t billionaires or aren’t friends with them). Instead of a straightforward path to becoming citizen-business owners supplying our local towns with bread, milk, clothing, medicine, vegetables, and other necessities; or individual researchers, inventors, craftspeople, and innovators with fair and open access to markets; we’ve instead been mostly relegated to the role of modern-day serfs: low-wage employees within top-down, bureaucratic private governments.

This sweeping economic reorganization, brought on by a blitzkrieg of deregulation and unfettered mergers, has us marching dangerously and ever closer towards the type of top-down, centralized, command-and-control economy its libertarian proponents claim opposition to. That is to say that our actual economic structure has very much begun to resemble a communist or fascist system, both of which by necessity demand centralized power and economic control, top-down organization, and a fusion of business and government. Both systems intentionally remove checks and balances, choosing instead to concentrate all power in a handful of elites in central command centers, and explicitly not in the hands of community leaders, small businesses, civic organizations, and individual citizens.

Before the pandemic, this reorganization was incremental but picking up steam. In the pandemic era, however, the pace of reorganization has accelerated far beyond what anyone could have imagined even a year ago. As small, independent, local businesses have folded by the tens of thousands, the growth of their highly capitalized corporate competitors has exploded, feverishly capturing ever more of the market share small businesses leave behind. Along with that expansion, of course, comes an ever-greater concentration of power and control over markets, information, individuals, and government policy.

Unchecked power has always led to the most intolerable abuses and atrocities humanity has experienced. And it’s categorically true to be the case going forward, tempting as it may seem at times to believe it’s simply a matter of getting the “right” sovereign in power. While an enlightened sovereign technically could, and in some historical instances has, improved the life of his or her subjects, the very opposite is just as likely and, as history proves, inevitable. Power is sought most judiciously by those who enjoy being powerful. And what the powerful most desire, always, is more power.

A representative democracy—composed of individual voters, state and local governments, small businesses, unions, and the like—is incredibly inefficient. It requires debate, discussion, hard work, and time to land on a shared consensus. This is true not just of identifying solutions, but also of recognizing and understanding what the reality of the situation is on the ground. This level of responsiveness, as it takes into account reports and ideas from a broad swath of individuals whose hands are actually on the problem itself, can be extremely inefficient in the short-term (meaning it moves slowly), but it can, like family farms, be extremely innovative, effective, adaptable, and resilient over the long term.

But even more importantly, it cannot be easily rolled up and controlled by an individual actor or cabal of actors.

On the contrary, one person can make a decision very efficiently. Let’s take Mark Zuckerberg, for example. With his 80% share of Facebook—a platform that itself directly touches billions of people around the world, and arguably through its influence on markets, discourse, and policy indirectly touches everyone—he can personally and efficiently decide how the algorithms should function on both FB and Instagram, as well as which posts are acceptable discourse. This is not technically censorship, as he is not technically the government. He can, however, as one individual, choose how billions of people across the world perceive and react to world events. Or if they see them at all. And this decision will ultimately have a sweeping impact on markets, elections, debates, and, as we’ve seen, violence in the streets.

Very efficient, yes. But it goes without saying that this is incompatible with democracy.

Having grown up in Ohio, before eventually moving away in search of meaningful employment of any kind, the despair and rage evident in many of Trump supporters, and the election of the man himself, is hardly a surprise to me. And though he certainly has, and has intentionally excited, a hardcore band of outright white supremacists, it’s reductive and ultimately unhelpful to paint such a broad brush across the entirety of the 75M people who voted for him.

A population that is captive to corporate control, powerless in their workplace and their own communities, and sneered at and looked down on as somehow deserving of their low-wage fate, will not hesitate to reach for any lever that looks even remotely viable to improve their lives. Really, any lever that promises anything to them at all.

The official narrative for so long has been that outsourcing and the loss of jobs, their jobs, and the loss in many cases of their family businesses and foreclosed homes, was simply “the market at work.” And that the government cannot, and should not, interfere with “the market.” Though the official narrative of both political parties for 40 years, at some intuitive level those who lost those jobs, businesses, and homes knew that couldn’t possibly be the whole story. And they were right, even if they, or we (and I’m including myself in here), haven’t understood exactly what could or should be done about it.

The fact that this official narrative, though pushed by both parties, has been hammered home incessantly by powerful media and leaders on the right is quite ironic. As well as the fact that it was Trump, speaking from the right, who broached a topic considered closed to discussion in official government discourse—that the government could possibly, just maybe, have a role to play in the economy. Though Trump’s catastrophic four-year run didn’t accomplish much of anything beyond inflaming division and driving our nation to the breaking point, his initial campaign actually did speak to the effect of things like trade treaties with China or the impact of NAFTA.

This is in no way meant to boost Trump—he’s shown himself to be a narcissistic charlatan whose only talent is public insults and braggadocio. I bring this up only because it’s critical we understand the ecosystem that spawned him, so we can avoid a repeat of the next Trump, who will almost certainly be worse.

I began writing this essay about our obsession with efficiency, and now I’m ending it with Trump. I find this to be unfortunate, as I hope you do as well. My suggestion is that the link between the two, and potentially far worse to come, is causal in nature, and inevitable in time. I believe we must understand the past policy decisions and cultural beliefs that got us to the present, if our democratic nation is to have any hope of a truly democratic future.

Great piece. I'll be sharing.

This article was absolutely phenomenal. I shared on my Facebook and I truly CONNECTED with what you were saying as someone who grew up in rural, central Wisconsin in the 2000s....Thank you so much for writing this thoughtful, meaningful piece.